➣ By Marjan Siadat & Rosemarie Fernandez

Trauma is the leading cause of death in the first four decades of life, with traumarelated injuries constituting more than 25% of all emergency department visits in the U.S. In 1980 the American College of Surgeons introduced the Advanced Trauma Life Support (ATLS) system as an evidence-based approach to providing trauma care. While ATLS does recognize the importance of team member interactions and leadership performance, far more time and attention is paid to technical skill development versus teamwork and team processes, e.g., communication, coordination, and situation monitoring. Unfortunately, review of the literature suggests that these teamwork competencies are critical to providing safe and effective trauma care.

Teams in Healthcare

Over 50 years of psychological research demonstrates that teams collectively possessing high levels of expertise, resources, and commitment to success can still fail without strong teamwork skills. Current literature goes a step further to state that, in fact, it is teamwork that guarantees effectiveness. In other words, the sum is only greater than the parts when teamwork is highly developed. This is especially true for interdisciplinary action teams such as aircrews, military command and control, and trauma teams where specialized expertise is required under uncertain and time-pressured conditions. Klein, et al. describe trauma teams as extreme action teams, “whose members (1) cooperate to perform urgent, highly consequential tasks while simultaneously (2) coping with frequent changes in team composition, and (3) training and developing novice team members whose services may be required at any time.” In action teams, the quality of teamwork and team effectiveness often means the difference between life and death.

In 2008 a multidisciplinary group of experts in healthcare and team performance met to propose a core taxonomy of teamwork competencies for emergency medical teams. This taxonomy was later adopted at the 2008 Academic Emergency Medicine Consensus Conference. While not specific to trauma teams, this taxonomy addresses the functions and processes critical for extreme action teams. Deficits in these key competencies, e.g., back-up behavior, coordination, communication, and leadership, have been shown to negatively impact clinical outcomes in trauma patients. Fortunately, the team literature demonstrates that well-designed training can improve team performance and mitigate errors in interdisciplinary action teams.

Healthcare Simulation-Based Training and Assessment

Simulation has been used in healthcare, aviation, and military team training. The term “simulation” spans a wide variety of formats, from the low-tech actor portraying a standardized patient to high fidelity mannequin-based human patient simulators and Virtual Reality (VR)-based task trainers. In fact, simulation includes any technology or process that recreates the contextual background of a healthcare environment, allowing providers the opportunity to experience an authentic clinical interaction with patients and other healthcare team members. Simulation-based training does not rely on chance encounters but rather creates a need for team interaction. Events begin with a “trigger” to activate the team and create the requirement for some type of team interaction. Well-designed event sequences are also careful to minimize the interdependence of performance quality. This allows educators and researchers to identify not only what happened (outcome measures), but also why it happened (process measures). As such, simulation can provide a platform for training and assessment that is diagnostic of individual, team, and, potentially, systems-based threats to ensure successful performance.

Simulation in Trauma Training

The use of simulation in trauma team training mirrors its use in aviation and other areas of healthcare, where the focus is interdisciplinary communication and interaction. Scenarios, whether created using a life-sized human mannequin or VR-based avatars, force participants to interact under time-pressured and complex conditions. Teams must then utilize their individual knowledge and teamwork skills to treat a patient(s) in an appropriate manner. Additional complications, such as power outages, mass casualties, and difficult coworkers can be brought into the scenario to meet training objectives. Simulations can target specific components of teamwork to help teams understand the various roles and responsibilities inherent in a trauma team. Such shared understanding (shared mental models) positively impacts team performance, especially under stress.

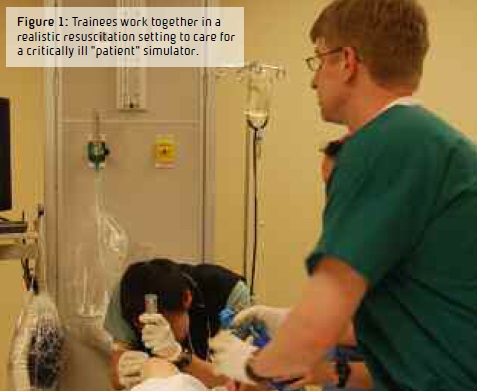

Mannequin-based simulation training has the advantage of allowing healthcare team members the opportunity for hands-on training. Events happen in real-time, often in an environment created to mimic a true emergency room or operating room setting. In fact, technology now allows for portable mannequins that can be brought directly into actual patient care areas, further enhancing the richness of the training experience by allowing trainees experience within their own system and with their usual equipment. In a small pilot study, Knudson, et al. demonstrated improved teamwork skills in individuals trained using mannequin-based simulation combined with didactic training versus didactic training alone. These results are supported by a study conducted by Falcone, et al., demonstrating improved trauma management of pediatric patients following multidisciplinary simulationbased trauma team training.

While mannequin-based team training holds significant promise for improving team performance, there are also limitations that are important to mention. First and foremost, high fidelity mannequinbased simulations can be quite costly, both from equipment and personnel (faculty trainer) standpoints. Simulation sessions are complex to develop, and as such, significant faculty time is required to develop each case. Additional costs are incurred when trainees are pulled from their work duties to participate in training, and often release time is difficult to obtain. Furthermore, mannequin-based training is, by design, hands-on. Training must therefore be done in small groups to allow team members the opportunity to interact as they normally would. This places an additional burden on faculty trainers, as many more faculty hours are required to conduct mannequin-based simulations versus a large lecture-based didactic session.

To address some of these limitations, researchers have turned to technology in the form of computer-based virtual worlds. Medical virtual worlds are housed on the Internet and use many of the features common in the gaming industry, including avatars. Trainees can therefore take on the role of an avatar and interact in a virtual patient care scenario as a physician, nurse, etc. Patient avatars (or robotars, if prescripted computer characters) provide opportunities for trainees to interact via their avatars. In this virtual world, teams can practice teamwork and trauma skills through their avatars from remote sites spanning the globe. Multiple patient triage, challenging environments, and tactical missions can all be programmed in to meet the objectives of the trauma training. Metrics, such as time to critical action (e.g., IV start, blood transfusion, etc.) or teamwork (e.g., communication, coordination of functions, etc.) can be assessed to provide measures of individual and team performance. Virtual world-based training is not hands-on and can be challenging for gaming novices, however, it does offer an alternative approach to team training that can overcome some of the logistical challenges inherent to large-scale mannequinbased training programs.

Marjan Siadat, M.D., M.P.H.

Rosemarie Fernandez, M.D.

Wayne State University School of Medicine

U.S.A.

marjansiadat7@gmail.com

fernanre@comcast.net

About Brenda Wiederhold

President of Virtual Reality Medical Institute (VRMI) in Brussels, Belgium.

Executive VP Virtual Reality Medical Center (VRMC), based in San Diego and Los Angeles, California.

CEO of Interactive Media Institute a 501c3 non-profit

Clinical Instructor in Department of Psychiatry at UCSD

Founder of CyberPsychology, CyberTherapy, & Social Networking Conference

Visiting Professor at Catholic University Milan.