➣ By Giuseppe Riva & Enrico Molinari

Figure 1: A patient undergoes experiential cognitive therapy

Different new technologies have been introduced over the last few years that are increasingly finding application in health care delivery for patients with eating disorders and obesity. These include self-help (supervised and unsupervised), telemedicine, telephone therapy, e-mail, Internet, computer software, CD-ROMs, portable computers, and virtual reality techniques. One of the most promising is virtual reality (VR), an advanced form of human-computer interface that allows the user to interact with and become immersed in a computer-generated environment in a naturalistic fashion.

Distorted body image, negative emotions and lack of faith in the therapy are typical features of these disturbances and are the most difficult characteristics to change. One innovative approach to their treatment is to enhance traditional cognitivebehavioral therapy (CBT) with the use of virtual reality.

A first approach is the one offered by the Experiential Cognitive Therapy (ECT). Developed by Giuseppe Riva and his group inside both the IVT2010 Italian Government funded project and the VEPSY Updated European funded project is a relatively shortterm, patient oriented approach that focuses on individual discovery. IET shares with the Cognitive Behavioral Therapy (CBT) the use of a combination of cognitive and behavioral procedures to help the patient identify and change the maintaining mechanisms. However it is different for:

- Its use of Virtual Reality (VR): 10 VR sessions are part of the standard protocol.

- Its focus on the negative emotions related to the body, a major reason patients want to lose weight.

- Its focus on supporting the empowerment process. VR has the right features to support empowerment process, since it is a special, sheltered setting where patients can start to explore and act without feeling threatened.

During the VR sessions (see Figure 1) they use the “20/20/20 rule.” During the first 20 minutes, the therapist focuses on getting a clear understanding of the patient’s current concerns, level of general functioning, and their experiences related to food and to the body. This part of the session tends to be characterized by patients doing most of the talking, although the therapist can guide with questions and reflection to get a sense of the patient’s current status. The second 20 minutes is devoted to the VR experience. During this part of the session the patient enters the virtual environment and faces a specific critical situation such as a kitchen, supermarket, pub, restaurant or gymnasium. Here, the patient is helped in developing specific strategies for avoiding or coping with the negative emotions induced by the situation. In the final 20 minutes the therapist explores the patient’s understanding of what happened in VR and the specific reactions–emotional and behavioral–to the different situations experienced. If needed, some new strategies for coping with the VR situations are presented and discussed. To support the empowerment process, the therapists follow the Socratic style–they use a series of questions related to the contents of the virtual environment to help clients synthesize information and reach conclusions on their own.

The different virtual scenes are included in an open source virtual environment–NeuroVR– that can be downloaded for free from the NeuroVR Web site: http://www.neurovr.org. Using this software the therapist may also customize each environment by adding significant cues such as images, objects, and video related to the story of the patient.

This approach was validated through different case studies and trials. In the first one, uncontrolled, three groups of patients were used–patients with Binge Eating Disorders, patients with Eating Disorders Not Otherwise Specified, and obese patients with a body mass index higher than 35. All patients participated in five biweekly sessions of the therapy. All the groups showed improvements in overall body satisfaction, disordered eating, and related social behaviors, although these changes were less noticeable in the Eating Disorders Not Otherwise Specified group.

More recently, the approach was tested in different controlled studies. The first one involved twenty women with Binge Eating Disorders who were seeking residential treatment. The sample was assigned randomly to ECT or to CBT based nutritional therapy. Both groups were prescribed a 1,200-calorie per day diet and minimal physical activity. Analyses revealed that although both groups were binge free at one-month followup, ECT was significantly better at increasing body satisfaction. In addition, ECT participants were more likely to report increased self-efficacy and motivation to change.

In a second study, the same randomized approach was used with a sample of 36 women with Binge Eating Disorders. The results showed that 77% of the ECT group quit bingeing after six months versus 56% for the CBT sample and 22% for the nutritional group sample. Moreover, the ECT sample reported better scores in most psychometric tests including EDI-2 and body image scores.

In the final study, ECT was compared with nutritional and cognitive-behavioral treatments, using a randomized controlled trial, in a sample of 211 female obese patients. Both ECT and cognitive-behavioral treatments produced a better weight loss than the nutritional treatment after a six-month follow-up. However, ECT was able to significantly improve, over nutritional and cognitive- behavioral treatments, both body image satisfaction and self-efficacy. This change produced a reduction in the number of avoidance behaviors as well as an improvement in adaptive behaviors.

A second approach was investigated by the Spanish research group led by Cristina Botella. Her group compared the effectiveness of VR to traditional Cognitive Behavior Treatment for body image improvement (based on the protocol developed by Cash) in a controlled study with a clinical population. Specifically, they developed six different virtual environments, including a 3D figure whose body parts (arms, thighs, legs, breasts, stomach, buttocks, etc.) could be enlarged or diminished (see Figure 2). The proposed approach addressed several of the body image dimensions–the body could be evaluated wholly or in parts, the body could be placed in different contexts, for instance, in the kitchen, before eating, after eating, facing attractive persons, etc., behavioral tests could be performed in these contexts, and several discrepancy indices related to weight and figure could be combined such as actual weight, subjective weight, desired weight, healthy weight, how the person thinks others see her/him, etc.

In the published trial eighteen outpatients, who had been diagnosed as suffering from eating disorders (anorexia nervosa or bulimia nervosa), were randomly assigned to one of the two treatment conditions–the VR condition (cognitive-behavioral treatment plus VR) and the standard body image treatment condition (cognitive-behavioral treatment plus relaxation). Thirteen of the initial 18 participants completed the treatment. Results showed that following treatment, all patients had improved significantly. However, those who had been treated with the VR component showed a significantly greater improvement in general psychopathology, eating disorders psychopathology, and specific body image variables. Since then, the group has also developed a VR simulator of food and eating currently under evaluation with patients. A final approach was proposed by the Spanish research group led by Gutiérrez-Maldonado. This group investigated the emotional potential of food-related VR experiences with eating disordered subjects. In a first study, thirty female patients with eating disorders were exposed to six virtual environments–a living-room (neutral situation), a kitchen with high-calorie food, a kitchen with low-calorie food, a restaurant with high-calorie food, a restaurant with low-calorie food, and a swimming- pool. After exposure to each environment the researchers evaluated the level of state anxiety and depression experienced by the sample. In a recent study, the response to the same five experimental virtual environments plus a neutral room in a group of eighty-five eating disordered subjects was compared with a control group of students. Results of several repeated measures analyses demonstrated that patients show higher levels of anxiety and a more depressed mood after exposure to high-calorie food and after visiting the swimming pool than in the neutral room. In contrast, controls only show higher levels of anxiety in the swimming pool.

Overall, these results show that virtual environments are particularly useful for simulating everyday situations that may provoke emotional reactions such as anxiety and depression, in clinical patients. Specifically, the virtual experiences in which subjects were forced to ingest high-calorie food induced the highest levels of state anxiety and depression.

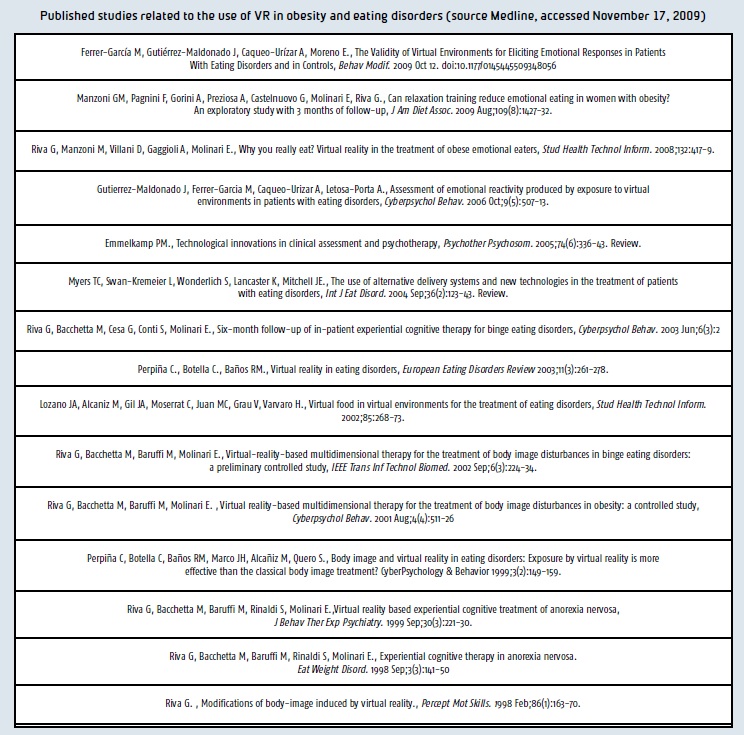

In conclusion, the data available on scientific journals (see Table 1) suggest that VR can help in addressing two key features of eating disorders and obesity not always adequately addressed by existing approaches–body experience disturbances and self-efficacy. VR technology offers an innovative approach to the treatment of body image disturbance, a difficult concept to address in therapy. Previously, cognitive-behavioral and feminist approaches have been the standard interventions, although in our experience, it seems that many patients continue to struggle with negative body image post-treatment.

Second, as emphasized by social cognitive theory, performance-based methods are the most effective in producing therapeutic change across behavioral, cognitive, and affective modalities. The proposed experiential approaches could help patients in discovering that difficulties can be defeated, so improving their cognitive and behavioral skills for coping with stressful situations related both to food and to their body.

Finally, the papers published by the Gutiérrez- Maldonado group suggest that VR may be useful, too, for simulating everyday situations to assess emotional reactions in clinical patients.

Giuseppe Riva, Ph.D.

Enrico Molinari, Ph.D.

Istituto Auxlogico Italiano

Italy

giuseppe.riva@unicatt.it

auxo.psylab@auxologico.it

About Brenda Wiederhold

President of Virtual Reality Medical Institute (VRMI) in Brussels, Belgium.

Executive VP Virtual Reality Medical Center (VRMC), based in San Diego and Los Angeles, California.

CEO of Interactive Media Institute a 501c3 non-profit

Clinical Instructor in Department of Psychiatry at UCSD

Founder of CyberPsychology, CyberTherapy, & Social Networking Conference

Visiting Professor at Catholic University Milan.