By Giuseppe Riva

The recent convergence between technology and medicine is offering new methods and tools for behavioral healthcare. Between them, an emerging trend is the use of Virtual Reality (VR) to improve the existing cognitive behavioral protocols for different psychological disorders, including the assessment and treatment of eating disorders.

The exact cause of eating disorders is unknown. Genetic, psychological, trauma, family, society, or cultural factors may play a role. In this context, VR offers different opportunities for the assessment of eating disorders. A first approach was proposed by the Spanish research group led by Gutiérrez-Maldonado. This group investigated the effect on body satisfaction – a key feature of eating disorders – produced by foodrelated VR experiences involving subjects with eating disorders. In a recent study, 85 female patients with eating disorders and 108 students were exposed to four virtual environments: a kitchen with high-calorie food, a kitchen with low-calorie food, a restaurant with high-calorie food, and a restaurant with low-calorie food. Results demonstrated that participants with eating disorders had significantly higher levels of bodyimage distortion and body dissatisfaction after eating high-calorie food than after eating low-calorie food, while control participants reported a similar body image in all situations.

In a different study a group of researchers headed by Alessandra Gorini recently tested whether virtual stimuli were as effective as real stimuli, and more effective than photographs in the anxiety induction process in these patients. Specifically, the study tested the emotional reactions, assessed using both psychological and physiological criteria, to real food, VR food (see Figure 1) and photographs of food in two samples of patients affected, respectively, by anorexia and bulimia nervosa compared to a group of healthy subjects. Real and VR food both induced a comparable emotional reaction in patients, higher than the one elicited by the photos. Instead, no differences were found in the healthy subjects. In summary, both studies suggest the potential of VR as an experiential assessment tool: only patients reported psychological and physiological changes after the exposure to VR food. This suggests the possible use of VR exposure as a screening tool in cases of suspected eating disorders.

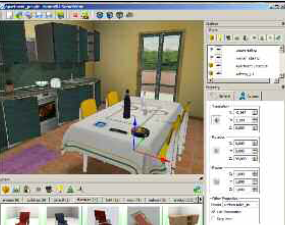

Figure 1: NeuroVR’s virtual environment has a limitless number of virtual scenes which can be customized by the therapist.

Distorted body image, negative emotions, difficulty in maintaining longterm positive outcomes and lack of faith in the therapy are typical problems of eating disorder patients. To target these issues, different groups are trying to enhance traditional cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT) with the use of a virtual environment.

The first approach is offered by Experiential Cognitive Therapy (ECT). Developed by Giuseppe Riva and his group inside the VREPAR and VEPSY Updated European funded projects, it is a relatively short-term, patient-oriented approach that focuses on individual discovery and proprioceptive changes. Alongside CBT, ECT shares the use of a combination of cognitive and behavioral procedures to help the patient identify and change maintaining mechanisms. However, it is different due to the inclusion of ten VR sessions. All the virtual scenes, included in a free virtual environment, NeuroVR, can be downloaded for free from the NeuroVR Web site, http://www.neurovr.org, and can be customized by the therapist adding significant cues (images, objects, and video) related to the story of the patient (see Figure 2).

Figure 2: Exposure to food in virtual

worlds can be used to measure the emotional

reaction of subjects, allowing for results to

aid in diagnosing eating disorders.

This approach has been tested in various controlled studies. The first involved 20 women with Binge Eating Disorders who were seeking residential treatment. The sample was randomly assigned to ECT or to CBT based nutritional therapy. Both groups were prescribed a 1,200- calorie per day diet and minimal physical activity. Analyses revealed that although both groups were binge free at one-month follow-up, ECT was significantly better at increasing body satisfaction, self-efficacy and motivation to change.

In a second study, the same randomized approach was used with a sample of 36 women with Binge Eating Disorders obtaining similar results. A second approach was investigated by the Spanish research group led by Cristina Botella. The group led by Botella compared the effectiveness of VR to traditional CBT for body image improvement in a controlled study with a clinical population. Specifically, they developed six different virtual environments, including a 3-D figure whose body parts (arms, thighs, legs, breasts, stomach, buttocks, etc.) could be enlarged or diminished and placed in different contexts (for instance, in the kitchen, before eating, after eating, facing attractive persons, etc.).

In a trial 18 outpatients, who had been diagnosed as suffering from eating disorders (anorexia nervosa or bulimia nervosa), were randomly assigned to one of the two treatment conditions: the VR condition (CBT plus VR) and the standard body image treatment condition (CBT plus relaxation). Patients treated with the VR component showed a significantly greater improvement in general psychopathology, eating disorders psychopathology, and specific body image variables. Furthermore, these results were maintained at one-year follow-up.

In conclusion, the present results encourage the use of VR in clinical (exposure therapy) and even non-clinical (task learning) settings in which a highly customizable and controllable simulation is preferred to a real-life experience.

Moreover, these results provide evidence of the potential of VR in a variety of experimental, training and clinical contexts, its range of possibilities being extremely wide and customizable. In particular, in a therapeutic perspective based on a cognitive behavioral approach, the use of VR instead of real stimuli facilitates the provision of very specific contexts to help patients to cope with their conditions. Finally, the results indicate that even a relatively cheap (less than 3000 ¤/4000 US$) PCbased platform using a VR software like NeuroVR can be used to screen, evaluate, and treat these patients.

Giuseppe Riva, Ph.D. Istituto Auxlogico Italiano Italy giuseppe.riva@unicatt.it

About Brenda Wiederhold

President of Virtual Reality Medical Institute (VRMI) in Brussels, Belgium.

Executive VP Virtual Reality Medical Center (VRMC), based in San Diego and Los Angeles, California.

CEO of Interactive Media Institute a 501c3 non-profit

Clinical Instructor in Department of Psychiatry at UCSD

Founder of CyberPsychology, CyberTherapy, & Social Networking Conference

Visiting Professor at Catholic University Milan.