➣ By Glen Bandiera

Medicine has a long tradition of learning within a clinical environment under the watchful eyes of experienced supervisors. While this model still forms the backbone of most post-licensure medical education, the old adage of experiential learning, “See one, do one, teach one,” has fallen by the wayside in favor of more controlled, deliberate, and evidence- based curriculum delivery. Medicine has been slow to take up simulation as a means to formalize learning, but concerns about patient safety resulting from physicians learning in practice, reduced resident work hours limiting opportunities for patient contact (and thus learning), and increasing evidence in support of competency-based education models have stimulated accelerated adoption of new methods. Thankfully technology, and more importantly, the fields of cognitive psychology and learning theory, have also risen to the challenge. Trauma care is particularly suited to the use of simulation. The dynamic, fast-paced and diverse practice of responding to acute severe injury combines elements of protocol-driven practice with quick information processing, complex decision-making and effective team management. Simulation shows promise to help with all of these dimensions of care, but the most effective use of simulation may not necessarily be the high-tech Virtual Reality wonders that might come to mind. Sometimes, simple solutions matched to specific educational needs are all that is required.

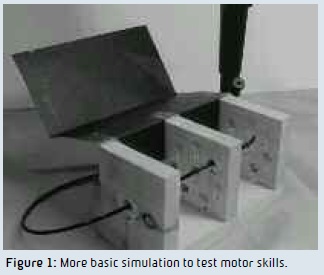

Effective trauma care is contingent upon skillful performance of procedures. High fidelity (life-like) part-task trainers (physical models simulating various body organs and cavities) have been developed and deployed to teach the mechanics of individual procedures with great effect. Even low fidelity models have been shown to improve subsequent performance of procedures on real patients (Figure 1). Such simulations can be delivered in a laboratory environment outside of a formal trauma resuscitation room and can be delivered to large numbers of learners at once, increasing the appeal. A common scenario involves a group of learners rotating from station to station with a different procedure at each station supervised by a senior faculty member. In addition to traditional measures such as time on task, error rates and global assessment of end results, technology has allowed the use of haptic responses, time-motion analysis, pressure sensing, and paucity of movement scales to gauge learner progress. The ability to create “variations on the normal” (e.g., anatomical variations or unanticipated swelling of the upper airway during an attempt to pass a tube into it) has been introduced to test a learner’s response to complications. In addition, portable technology has allowed computerized mannequins to be embedded into a real environment (for example, placed in a real emergency department treatment room to carry out a pre-planned specific simulated case during a regular shift) or into non-traditional educational environments such as a simulated mass casualty incident in a local gymnasium.

Beyond the procedures themselves, decision- making is critical to successful trauma care. To effectively teach and assess this, it is desirable to replicate the clinical environment as closely as possible, and computerized high fidelity simulation clearly is the preferred choice. Learners must be able to recognize the context, there should be minimal need for them to suspend disbelief, and most importantly, they must be able to translate what they learn back and forth from the simulation lab to real life. Mock trauma resuscitation rooms and trauma operating theaters are easily created and a single simulation lab can be converted from one to the other in about 30 minutes. When outfitted with all necessary medical equipment and equipped with relevant real-time monitoring and online operator control (to allow a tailored response to learner actions), almost any clinical contingency can be replicated to test a learner’s ability to think on the fly. As important as the technology are the cases used for teaching, including detailed goals and objectives for the case, precise scripts and roles for all participants, and clear expectations for performance including, if in an evaluative setting, what constitutes satisfactory versus unacceptable performance. The development of such cases requires considerable time and expertise and has been a major limiting factor to the effective deployment of simulation as a teaching and evaluation method. Advances in these areas, informed by curriculum development theory and supported by on-line repositories and libraries, have helped the field move forward in recent years.

More than anything, trauma care is about teamwork and simulation has been successfully adopted to test teams, rather than individuals. Despite the fact that individuals from multiple healthcare professions are expected to work together in practice, true interprofessional education, wherein practitioners from these disciplines learn with and from each other, is new. Simulation has provided an opportunity to embrace this form of education and focus on skills that have until recently not been explicitly taught. Crisis resource management techniques, adopted from the airline industry by the specialties of anesthesia, critical care and emergency medicine/trauma, have formed an appealing basis for establishing performance and evaluation standards for teams. Designing scenarios and evaluating the participants not on individual decision-making and technical skills but rather on communication, interpersonal dynamics and role awareness, is seen as a ripe frontier and is the focus of ongoing research in medical education.

Finally, simulation has allowed researchers to further their understanding of how certain factors in a learner’s environment can affect learning and performance. Until the advent of realistic simulation, it has been difficult to sufficiently create and control an environment for experimentation of this type to take place. One particularly interesting line of research is into the effects of stress on learner performance. By measuring perceived stress using validated questionnaires and physiologic stress using salivary cortisol levels, it has been shown that careful variations in a scenario can significantly vary the stress experienced by a participant without necessarily changing the complexity of the decisions, procedures or medical care required. Researchers have shown that increased stress can have a negative impact on performance of complex cognitive tasks and that this effect can be minimized with repeated exposure. These findings have huge implications for the role of repeated exposures, desensitization protocols and explicit stress mitigation teaching that has thus far not been part of most medical education curricula.

For complex, high stakes fields like trauma care, where the real environment is unpredictable and hard to control, simulation has proven to be an invaluable aid to educating the future generation of practitioners. With ongoing focus and judicious deployment, we can expect safer, more evidence-based education and care in the future.

Glen Bandiera, BASc, M.D., MEd, FRCPC

St. Michael’s Hospital

Canada

bandierag@smh.ca

About Brenda Wiederhold

President of Virtual Reality Medical Institute (VRMI) in Brussels, Belgium.

Executive VP Virtual Reality Medical Center (VRMC), based in San Diego and Los Angeles, California.

CEO of Interactive Media Institute a 501c3 non-profit

Clinical Instructor in Department of Psychiatry at UCSD

Founder of CyberPsychology, CyberTherapy, & Social Networking Conference

Visiting Professor at Catholic University Milan.